Media

Ocean acidification study offers warnings for marine habitats

Calcifying mussel beds and coral reefs particularly vulnerable

22 Nov 2016

Acidification of the world’s oceans could drive a cascading loss of biodiversity in some marine habitats, according to research published recently in Nature Climate Change.

The work led by biodiversity researchers from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and with contributions from colleagues in the University of Hong Kong (HKU) as well as in the U.S., Europe, Australia and Japan, combines dozens of existing studies to paint a more nuanced picture of the impact of ocean acidification.

It has been known for some time that there will be big losers and some winners with climate change and ocean acidification, both driven by increasing carbon emissions.

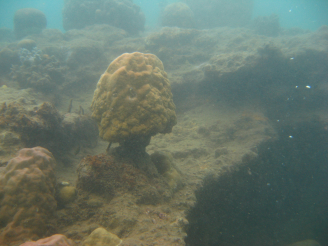

While most research in the field focuses on the impact of climate change and ocean acidification on individual species, this new work focused on the impact of ocean acidification on living habitats, such as coral reefs, mussel beds, kelp forests and seagrass meadows that form the homes of thousands of marine species. The researchers used observations of altered habitats around the world to make predictions about how changes in these habitats brought on by ocean acidification will impact the number of species that each habitat can support.

The researchers combined data and observations from 10 field studies that measured the impact of underwater volcanic vents, which release carbon dioxide and mimic the conditions of future ocean acidification, on the density of habitat-forming species. They combined these data with 15 studies looking at how changes in habitat typically impact local species to make their predictions.

“Not too surprisingly, species diversity in calcium carbonate-based habitats like coral reefs and mussel beds were projected to decline with increased ocean acidification,” said UBC zoologist and biodiversity researcher Dr. Jennifer Sunday, who led the study. Species that use calcium carbonate to build their shells and skeletons, like mussels and corals, are expected to be particularly vulnerable to acidification.

Large declines in coral reef biodiversity expected

“We know from locations where volcanoes acidify the seawater that the structure of coral reefs could be dissolved by future ocean acidification and that this loss of habitat will cause large declines in reef biodiversity,” said Dr Bayden Russell, a researcher at The Swire Institute of Marine Science (SWIMS), HKU, and co-author on the paper.

The researchers were able to test their predictions against real-world data from two sites: a coral reef near Papua New Guinea and a group of seagrass beds in the Mediterranean, both where carbon dioxide from active volcanos acidifies the ocean. In the case of the coral reef, the diversity and complexity of marine life in the area decreased as acidification increased. Despite predictions that the seagrass beds would fare well under increased levels of carbon dioxide, no increases in biodiversity was observed.

Seagrass shows complex responses

“The more complex responses are those of seagrass beds that are vital to many fisheries species. These showed the potential to increase the number of species they can support, but the real-world evidence so far shows that they’re not reaching this potential. This highlights a need to focus not only on individual species, but on how the supportive habitat that sets nature’s stage responds and interacts to climate change,” said Jennifer Sunday.

Mussel production will show a decline

According to this study, natural reefs built by the mussels on the northwest coast of the USA are similarly predicted to decline in abundance, with the associated decline in biodiversity, under future acidification.

“Now we have a much clearer picture of how some losers can drag biodiversity down with them, and how some other species might be able to help their habitat mediate a response to acidification For example, in the Pacific Northwest, the number of medium to large-sized edible saltwater mussels is likely to decrease as the chemistry of our oceans changes, and this is bad news for the hundreds of species that use them for habitat,” said UBC marine ecologist Professor Christopher Harley, senior author on the paper.

“While mussels do not create natural beds in Hong Kong like other parts of the world, it is likely that mussels in aquaculture will be affected in a similar way and show a decline in production,” said Dr Russell.

“Although they were not part of this study, we are also concerned about the future of oysters in Hong Kong” commented Dr Vengatesen Thiyagarajan, a researcher at SWIMS, HKU. According to Dr Thiyagarajan, like mussels in USA, oysters in Hong Kong and mainland China are well known for the production of seafood, health supplements, and for providing multiple ecosystem services.

Because there are so few test sites to use to directly test the model, the authors want to expand on the approach.

The article “Ocean acidification will mediate biodiversity shifts by changing biogenic habitat” published in Nature Climate Change is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3161.

Media enquiries:

Associate Professor of the School of Biological Sciences Dr Bayden Russell (Tel: +852 6509 3351/ +852 2299 0680; email: brussell@hku.hk);

Associate Professor of the School of Biological Sciences Dr Vengatesen Thiyagarajan (Tel: +852 22990601/ +852 28092179/ +852 95757923; email: rajan@hku.hk);

Faculty of Science Ms Cindy Chan (Tel: +852 3917 5286/ +852 6703 0212; email: cindycst@hku.hk).