Media

Geologically recent sea-level fluctuations add new twist

to evolution story on “Darwin’s archipelago”

25 Apr 2014

The 16-island Galapagos archipelago in the eastern equatorial Pacific host one of Earth’s most important biodiversity hot-spots. Famously, the land birds and reptiles provided Charles Darwin with key insights into Natural Selection, the mechanism that drives biological evolution. Today, the volcanic chain is arguably Earth’s greatest natural biological laboratory attracting researchers from across the World who “mine” the animal and plant repository looking for ever deeper understanding.

Oddly, although most scientists are happy with the notion that the original ancestors of each of the reptile groups (tortoises, snakes, land iguanas, lava lizards, geckos) rafted/floated in from the Americas more than 900 kilometers to the east, few consider how the descendents came to be scattered across the archipelago. Their investigations focus on the present, the broader story apparently irrelevant.

Now, new research by the University of Hong Kong earth scientist, Dr Jason Ali, and his University of Sydney geologist colleague, Prof. Jonathan Aitchison, is set to dramatically alter our view of Galapagos’ biology. Their work offers a comprehensive explanation as to why certain species are present on particular islands and absent from others, and how they got there. The investigation, however, carries a twist for it provides a radical new insight into the evolutionary development of a key fraction of the island chain’s species.

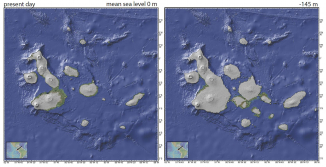

The study, to be published in the Journal of Biogeography, indicates that major shifts in sea level, caused by various climatic and geological processes, regularly reconfigures Galapagos’ geography. The extreme lows drop the shore-lines somewhere between 130 and 210 metres. At these times, the islands in the centre and west of the chain (“core”) coalesce into a mega-platform as illustrated in Figure 1 below. During these 10,000 year connection intervals, the long-isolated reptile forms are free to move around the new landmass. However, the sea-level rises that follow force them back on to higher ground where they are genetically trapped for around 90,000 years.

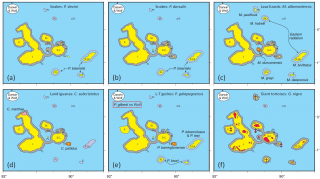

Key to understanding the overarching biological patterns and, crucially, any anomalies was Ali and Aitchison’s realization that the various reptile forms might respond differently to their periodic “unleashing”. They thus constructed a series of logic models to help interpret the data. The two most important ones considered the outcomes if (1) the reptiles could fully colonize the newly exposed landmass or, (2) if they were only able to expand their ranges by limited amounts. Critically, both make specific predictions, hence assigning each of the reptile forms to a particular category was thought to be straightforward. With scenario 1, “everything gets everywhere”, and this accounts for the two racer snake species, as shown in Figure 2 below. With scenario 2, speciation is likely to take place on the peripheral/ less accessible platform islands, whilst species reconsolidation will occur on the more central ones. This accommodates the lava lizards, land iguanas and geckos.

Curiously, Galapagos’ legendary giant tortoises are the only land-bound reptiles that cannot be explained by the modeling as they appear on the “core” and non-core islands. Research carried out by molecular biologists indicates that their gene pools are hugely complex. It suggests that members of the various sub-populations were regularly swimming/floating between islands and thus sharing their genetic material with their closely related neighbours. Moreover, in recent centuries, the tortoises, which were prized for their meat, were moved between islands by sailors and pirates for use as food stashes. Hence their story has an extra level of complexity.

A fundamental tenet of any scientific hypothesis is that it is amenable to testing and Ali and Aitchison have taken great care to outline one.

Prior to the DNA revolution, scientists related species to one-another by comparing their body parts – an investigative discipline called comparative anatomy. The more similar organisms looked, the more closely they were thought to be related. In cases where it is obvious, for instance humans are nearer to hamsters than they are to hammerhead sharks, the technique still works.

For allied forms, however, working out their relationships is less easy. Such is the case with the hundreds of cichlid-fishes species in the East African lakes, or the dozens of nocturnal lemurs in Madagascar. Thus, biologists today often construct “family-trees” using differences in the species’ DNA: the bigger the divergence, the greater the time since the two shared a common ancestor.

Therefore, if the Galapagos model is correct, then the ages of the family-tree branch points for the various reptile species and subspecies should immediately post-date the ages of the various sea-level lows (20 k years, 138 k years, 252 k years, 342 k years etc). Shortly after these instants, populations on different patches of high ground were genetically isolated by the rising oceans. Crucially, this pattern should be easily discernible in future DNA molecular “clock” researches.

Galapagos’ biota has long been recognized as special. Ali and Aitchison’s proposal that a key part of the archipelago’s biota has been forged in such a distinctive manner makes it even more so. Moreover, there are only a small number other island systems where the same process could have played out, perhaps the Canary, Cape Verde and Maldive groups. In all three cases, though, far fewer islands are involved. Galápagos is thus a truly unique biological laboratory; the study increases its significance as a scientific resource and enhances its conservational value.

For the abstract of this research paper, please click here.

For media enquiry, please contact:

Dr Jason Ali, Department of Earth Sciences (Tel : 2857 8248 / 5301 3937; Email:jrali@hku.hk; Skype: jason62ali; or Rhea Leung, Communications and Public Affairs Office (Tel : 2857 8555; Email : rhea.leung@hku.hk)